Does the Natural Medicine Health Act Threaten Indigenous Communities?

Recommended reading:

Natural Medicine Colorado: Combining Regulated and Community Healing Models

Colorado Prop 122: A Transformative Measure Grounded in Equity and Healing

Why Coloradans Should Vote NO On The Natural Medicine Health Act

Native coalition against Colorado Natural Medicine Health Act

The Complicated Ethics of Legalizing Indigenous Psychedelic Substances

This week Colorado voted “YES” to allow access to psychedelic experiences. The Natural Medicine Health Act enables licensed facilities to offer individual and communal healing through psilocybin. It allows people to grow, hold, ingest or gift certain hallucinogenic plants and fungi without fear of punishment.

While 53.4% of Coloradan voters may be proponents of the bill, the remaining population isn’t convinced this is the right step forward. I feel each oppositional argument is worthy of its own essay and discussion.

However, I’d like to focus on one of the most controversial implications of the proposition, which arose in discussion amongst members of my community and has been voiced more publicly by The Native Coalition Against the Natural Medicine Health Act. This group, formed in opposition to the NMHA, says the bill “stands to threaten, exploit and commercialize Indigenous peoples and spiritual traditions.”

Given the injustice and extortion modern American society has imposed on indigenous people throughout recent centuries, it would be hard to imagine anyone identifying as indigenous not feeling heightened skepticism towards the fast-moving evocation of commercialized phytotherapy.

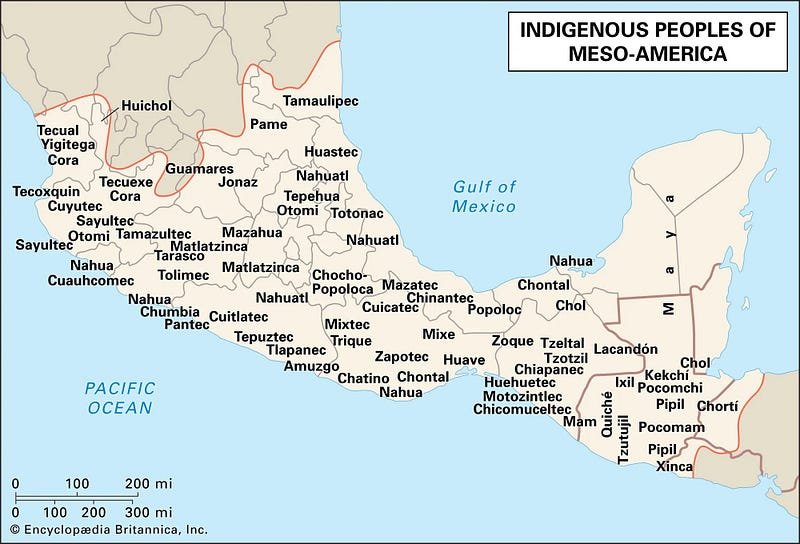

For example, some psilocybin rituals originated in groups of Nahua, Mixtecs, Mixe, Mazatecs, Zapotecs, and other communities native to the territory we now call Mexico.

Indigenous Peoples of Meso-America. Source: Encyclopedia Brittanica

Famously, María Sabina[1] (1894–1985), a Mazatec woman from the Oaxaca region is cited as the first indigenous curandera[2], shaman[3], and poet to share her ancestral wisdom, along with the specific mushroom species she used in ceremony, with a Westerner.

R. Gordon Wasson — an American author and ethnomycologist — and his wife Valentina Pavlovna[4] cultivated a relationship with Sabina in order to learn from her practices and collect spores of the fungus (Psilocybe Mexicana) for scientific examination and synthetic development in Europe.

Wasson later admitted to deceiving Sabina during their interaction as a way to gain her trust and the closely-held secrets of her ancestral practices. Following the publication of Wasson’s discoveries in the 1960s, her townhood received a flood of mushroom-seeking tourists; followed by interrogation from Mexican police suspecting her to be a drug dealer; the burning down of her house; and sadly the murder of her son, all as Sabina was ostracized from her community.

I reference this chapter in history because it is often considered the pivotal moment that led to western society gaining access to the “power of the sacred mushrooms”, with grave consequences[5] to the teachers in each story. Countless historical records of a similar extractivist western maneuver were bound to become the premise of concerns often voiced towards initiatives like NMHA, and the current of fear that fills the air in many related conversations.

—

Disclaimers

I do not believe my perspective is the truth. I’m male, white caucasian, and born in the safety of the United Kingdom. I had the privilege of financial security and education as a child, some benefits of which I’m aware while understanding there must be so many more I can’t see.

However, I have spent many years embedded in the psychedelic medicine space. Learning from and with some of the most thoughtful, wise, and respected figures underpinning this movement. As a keen listener, I’ve cultivated a vantage point that I hope is fair and all-inclusive.

Before publishing, I shared drafts of this essay with several such figures who I honor for their dedicated years of work on this topic. I’d like to thank Kevin Matthews, David Bronner, Joshua Kappel, Sean McAllister, Amanda Efthimiou, Jaz Cadoch, and Reilly Capps for their valuable input.

To quote Blaise Pascal, “if I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter”. I welcome dialog if you feel anything that I share was written in ignorance, or without mindfulness of your unique perspective.

With that, let us explore the question and enrich this historic moment with curiosity…

Does the Natural Medicine Health Act Threaten Indigenous Communities?

Let’s dissect this question into more specific parts, including

Which concerns have been raised publicly on behalf of indigenous communities?

How have Natural Medicine Colorado and NMHA been addressing indigenous concerns?

Are Psilocybin, DMT, Ibogaine, and Mescaline being treated similarly by this bill?

What is the nature of the relationship between psychedelics and indigenous communities?

Can psychedelics themselves help us reconcile the differences in opinion surrounding this bill?

1. Which concerns have been raised publicly on behalf of indigenous communities?

For a descriptive list of concerns published by the Native Coalition Against Colorado Natural Medicine Health Act click here. The following concerns have been raised in channels and circles I access, intentionally summarized in single sentences for brevity. The Natural Medicine Health Act could be:

Disregarding or diluting ancestral traditions through gentrification;

Giving power over plant medicines to the state, and specifically to white, cis-gender men;

Threatening the opportunity for indigenous people to offer psychedelic healing above-ground;

Creating more competition for indigenous healers in the marketplace;

Disrespecting the spirit of these natural medicines through commodification;

Encouraging extractivism through unsustainable harvesting of natural compounds;

Corrupted by capitalist incentive systems;

A hasty approach has not allowed us enough time to act in everyone’s best interests;

Of these, the most commonly cited is the last. Given the ancestral wisdom passed down through generations, there is a longitudinal quality to the indigenous perspective, which contrasts hastier ways of thinking in the modern Western world.

This mindset has allowed for innovation within very fast timelines. For many of us born into this paradigm, it’s all we know. Just as a toddler acts upon the impulse of a few minutes, while an elderly person may act upon the impulse of several decades, I wonder whether younger and older cultures are destined to act at a velocity corresponding to their own timelines; or whether slowness — even stillness — is available to all.

2. How have Natural Medicine Colorado and NMHA been addressing indigenous concerns?

For many months, the community has gathered across meeting rooms, on zoom screens, around dinner tables, and in town halls to examine and debate the facets of this complex topic.

I’m told by an NMHA steering committee member that leaders of the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Ute, and Southern Ute tribes were approached at the beginning of the drafting process to assemble collaborative input. Let me be clear that this is an unconfirmed statement and I’m also told by opponents that there was a lack of diligence in seeking the input of enough representatives from these and other tribes.

Chacruna, an organization well-respected in fostering awareness and support for indigenous perspectives shared in a recent article[6] “the initiative was developed with an extensive community input process that many critics participated in”, continuing, “NMHA does exactly what community activists requested: decriminalization first, regulation later, exclusion of peyote, and extensive social justice sidebars.”

Peyote[7] is a mescaline-producing cactus that takes many years to grow and has been used in the ceremonial practices of these tribes for generations. However, psychoactive mushrooms were used sparsely by local indigenous communities until the recent cross-pollination of South, Central, and North American peoples. For this reason, I’m told, many indigenous leaders approached by Natural Medicine Colorado were agnostic to the outcome of psilocybin policy reform in Colorado.

David Bronner[8] shares that “while it’s been an intense process, the NMHA has been deeply informed by individuals and groups subjected to historical and ongoing exploitation and injustice, in dialog with groups committed to allyship and positive change, towards healing for all.” He says that The Native American Church and National Congress of American Indians have emphasized the sustainability risks of decriminalizing mescaline sourced botanically from peyote cacti, urging policymakers to omit this species from drug law reform. “Supporting all the peyote-using tribes north and south of the border in their efforts to conserve and protect their medicine for the generations to come, is a central task of the Indigenous Medicine Conservation Fund that is launching this spring.”

The debate continues as more representatives of indigenous communities enter the conversation. And as the NMHA establishes the mandated Natural Medicine Advisory Board, they are required to appoint at least one indigenous representative and to “annually report on impacts to keystone medicines and indigenous cultures”.[9]

3. Are Psilocybin, DMT, Ibogaine, and Mescaline being treated in the same way by this bill?

Proposition 122 decriminalizes the personal use and possession (for adults age 21 and older) of the following hallucinogenic/entheogenic plants and fungi, which are currently classified as Schedule I controlled substances[10]:

dimethyltryptamine (DMT);

ibogaine;

mescaline (excluding peyote);

psilocybin; and

psilocin.

The intention is to innovate upon the current legal framework, under which a significant number of people — disproportionately people of color and from marginalized communities — have been incarcerated for personal decisions to carry or consume an often organic plant or mushroom while causing no harm to others or society. This paradigm’s impacts have been costly to the state and its taxpayers, and nonrehabilitative to the individuals and communities most burdened by this establishment.

The new framework[11] allows anyone aged 21 and older in Colorado the limited personal possession, use, and uncompensated sharing of ‘natural medicine’. There will be specific protections under state law, including criminal and civil immunity, for authorized providers and users of natural medicine. Anyone previously convicted of a crime relating to personal use or possession of such plants and fungi will be able to file a petition asking the court to seal their criminal record. The proposition also limits the State’s ability to declare child abuse or neglect or restrict parenting time due to possession of plant medicines.

Noting an understandable comparison to the recent cannabis reform, it’s worth underlining that none of these molecules will be sold in shops or dispensaries. As an entrepreneur working in the cannabis industry from 2014–2018, I supported the freedom Colorado offered for people to try marijuana without fear of prosecution or separation from their families. I also learned from the consequences of such a liberal and fast-paced approach, in which potent psychoactive plants are sold as consumer packaged goods.

Inevitably, many of the well-meaning companies that strove to bring these products to market were beholden to shareholder interests. Two predictable byproducts were 1) the trend towards lower prices and often lower production quality, and 2) higher potency products, which have increased the risk of harm when not deliberately accompanied by authentic education.

This may be the most important and overlooked distinction between the cannabis reform of 2012 and the psilocybin reform of 2022. The focus on services rather than products not only generates a safer environment for society to engage with previously stigmatized compounds but also disincentivizes the corporate interests that overwhelmed an otherwise promising social experiment with cannabis.

Source: Unlimited Sciences

Source: Chronogram

Proposition 122 establishes “a natural medicine regulated access program for supervised care, requiring the department of regulatory agencies to implement the program and comprehensively regulate natural medicine to protect public health and safety”[12].

This regulated approach is referred to as “communal healing,” a methodology that has been integral to human societies throughout history and is increasingly accepted as a valid therapeutic modality in the academic literature[13]. David Bronner articulates this framework well in his recent post for Dr. Bronners.

However, it’s vital to note that only Psilocybin[14] and Psilocyn[15] will be allowed for consumption in these licensed healing centers. The remaining compounds (ibogaine, mescaline, DMT) may only be introduced to healing centers starting in 2026. This approach gives the community a three-year period in which our community — including all members of society who engage with it — can learn from the initial roll-out of psilocybin and psilocin services.

This approach also creates a set of protections for Colorado in the event that biotechnology companies such as Compass Pathways bring psychedelic medicine through Phase III FDA trials. Corporate interests are aligning their sights on for-profit medical models that would irrevocably limit the type of democratic and affordable access that NMHA strives to create. Regardless, it is conceivable that biotech companies such as Compass will bring psilocybin pharmaceuticals to market across the USA by 2024, creating top-down regulation via the prescription framework. To re-state the point, this would directly limit opportunities for state initiatives to establish alternative models of access to plant medicines.

As one NMHA member told me, “NMHA is both a buffer to protect these medicines and the civil liberties for people to use them here, along with creating a diversity of access options in the near future that lets the marketplace decide.”

4. What is the nature of the relationship between psychedelics and indigenous communities?

I believe we have to look more deeply to make truly thoughtful decisions about the ethics of psilocybin drug policy in Western society. Let’s consider this further after reviewing the origins of Psilocybin and other plant medicines throughout history.

Psilocybin is the psychoactive compound in roughly 200 mushroom species[16], produced by nature for many thousands of years. While Mexico has the greatest concentration of psychedelic mushrooms (53), many other species are found growing naturally in North America (22), Australia and its surrounding islands (19), Europe (16), Asia (15), and Africa (4).

Murals in Algeria, Africa — dated 9000 to 7000 BCE — depict anthropomorphic beings holding mushrooms while running or dancing, dotted lines connecting the mushrooms to the tops of their heads as though to emphasize an ethereal connection of ideas. Similar depictions in the region are thought to represent shamanistic rituals and processions.[17]

Source: G. Mütrel, Leipzig ; Berlin ; Wien : F.A. Brockhaus, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The oldest record suggesting ritualistic psilocybin use by humans is contained in prehistoric rock art near Villar del Humo in Spain, dating to 6,000 years ago.

These are signposts along a path of psychoactive mushroom use throughout human history. This long path spans from Western Australian rock art c. 10,000 BCE[18] to the prehistoric artworks of Spain c. 4,000 BCE, to the Ancient Egyptian tales of Psilocybe Cubensis mushrooms being cultivated on grains and attributed to Osiris, the God of spiritual rebirth[19], to the use of Amanita Muscaria in Siberia to induce euphoria, strength, and stamina[20], to the first mention of hallucinogenic mushrooms in European medicinal literature in the London Medical and Physical Journal in 1799.

It is evident that the indigenous Mesoamerican traditions most directly informed our contemporary rituals involving psilocybin It is only reverent to acknowledge the connection between humans and mushrooms that pre-dates this chapter in history.

Steward of the El Puente foundation, Amanda Efthimiou told me “magic mushrooms in my view are an inclusive medicine with diversity of origin and tradition. Although many of us attribute their stewardship to the Mazatec people of Mexico, they are not and were not the sole guardians for their use, therapeutically or otherwise.” With this in mind, it’s worth us pondering whether rituals, practices, or behaviors of any kind can possibly ‘belong’ to any one group, given the long lineage of co-discovery and cross-cultural inspiration weaving through humanity.

5. Can psychedelics themselves help us resolve the differences in opinion surrounding this bill?

Maria Sabina herself believed “there was no opposition between traditional medicine and Western medicine, but rather a complementary relationship. She also held this to be the case with the spirituality coming from the Mesoamerican tradition and the tradition coming from Christianity. On one occasion, María Sabina was shot twice and taken to the village doctor, a young man called Salvador Guerra. He used anesthesia and removed the bullets. She was amazed and grateful to the doctor, and they later became friends. She even performed a mushroom ceremony for him.”[21]

Source: Cosmic Maria Sabina by Juan Oaxaca

This story nods to the potential for even an indigenous person as negatively affected by extractive capitalism as Sabina to acknowledge the inherent interchange between cultures. A place from which she could express her gratitude for Western innovation alongside the wisdom of her own people. She embodied — and inspired the rest of us to achieve — the ‘overview effect’[22]. A state of awe, wonder, unity, and interconnection that is equally available from altered states of consciousness as it is from the sublime view of the earth, described by the astronauts of space travel.

This sentiment echoes one of the most common realizations borne by psychedelics themselves: the feeling and experience of unity with all beings and nature. Common-unity. Community.

This feeling of unity[23] — also described as ‘ego-dissolution’ — may be caused by a reduction of the ego’s sense of separateness. A diminishing of self-importance and conceit[24].

Scientific brain scans reveal the neurobiological causes of this phenomenology[25]. Activity in certain regions of the brain slows down. These regions evolved to help us survive by individuating and becoming competent at looking out for ‘ourselves’ in a dangerous world full of predators and rival tribes. Some would argue this function of the mind is decreasingly helpful as we co-create a civilization with fewer extrinsic threats and a desire for greater peace.

“Thinking fragments reality. It cuts it up into conceptual bits and pieces. The thinking mind is a useful and powerful tool. But it is also very limiting when it takes over your life completely. When you don’t realize that it is only a small aspect of the consciousness that you are.” — Eckhart Tolle

Meanwhile, mystical experiences are induced by psychedelics in part thanks to this reduction of default thought patterns; in part, because they help us generate neurons and synaptic connections to convey novel thought patterns across the regions of our brain.[26]

A growing body of research supports the hypothesis that psychedelics can generate a greater sense of connectedness to other people and nature. One study involving over 1,200 participants across six multi-day gatherings in the United States and the United Kingdom concluded that “psychedelic substance use was significantly associated with positive mood […] and increased social connectedness.”[27] Another study[28] by one of my colleagues at Maya, Hannes Kettner, and his team surveyed 150 psychedelic users and found that all reported an increase in connection to nature, with two-thirds stating their environmental concern had increased.

But we have to ask: would this be the case had these participants been given psychedelics strictly in controlled scientific settings or in medical clinics? Researchers at Imperial College surveyed 654 participants and published a paper stating that “an increased acknowledgment of nature has also been implicated in enhancing psychological connectedness in a broader sense, including connectedness to other people, nature, and life in general.” They go on to say that “arguably, by meaningfully connecting with nature during a psychedelic experience (especially so if the experience is within the context of pleasing natural surroundings), otherwise healthy individuals may be enticed to spend more time in nature in the future, thereby adopting a healthier, more nature-related lifestyle.”[29]

Colorado’s innovation could create the grounds for us to understand these phenomena more clearly, by learning from people’s natural experiences, many of which will be held at healing centers designed to fully incorporate nature. It is now possible for the healing centers of our near future to look and feel different from the normative clinical containers.

This environment brings together two polarized arms of the psychedelic movement: the left hand holding underground recreational psychedelics; the right hand gripping research in the laboratories of Academia and Pharma. I believe we are going to benefit from these hands coming together, to cultivate closer communication, cultivate safer and more accessible environments, and discover best practices. Because we are passed the point of asking whether psychedelics can help people; I believe we can now graduate to asking how they can help people in the safest, most accessible, and most powerful ways.

The psychedelic industry is already becoming a bastion of proactive reciprocity. Initiatives such as North Star, Chacruna, Journey Colab, El Puente, River Styx Foundation, and many others have paved the way for this community to ask the right questions and cultivate new channels for cross-cultural dialogue.

IRI, the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative, is a grassroots network of 20 Indigenous community-led organizations addressing everything from “food security and environmental health to economic and educational access to land tenure and cultural conservation, and more.”[30] The organizations listed on their website span North, Central, and South America and represent the opportunity for people in all regions to unite towards a common goal of listening, learning, understanding, and ultimately supporting each other.

Conclusion

As I’ve spent more time researching and learning from a range of thought leaders for this essay, I’ve come to realize that the request from indigenous spiritual and political leaders is often for us “to truly listen”, which perhaps can only happen with more time.

This implies a mindset shift that departs from the typical Western approach to progress, usually emphasizing action, doing, and movement. The NMHA has rational and defensible reasons for acting now; namely to protect Colorado from the burgeoning biotech industry and the restrictions that big pharma tends to place upon truly equitable access to the types of healing that are offered by plant medicines.

However, I believe we all have an opportunity to evolve as a society if we embrace the plants and the inner and collective wisdom they help us access, and then dedicate the time and energy to embody these realizations through cooperative integration. It is an inherent part of being human that we all see things differently. This phenomenon creates contrast that activates life and stretches the fabric of our conscious experience, but it doesn’t need to create conflict.

Does the Natural Medicine Health Act Threaten Indigenous Communities?

I don’t think this question has an objective answer, and perhaps this isn’t even the appropriate question to ask, so I commit to listening. Listening to the ideas of all who are involved in the rollout of this initiative, as well as those who feel they have been left behind by it. Because I believe that despite our missteps, compassion in contentious moments like this will illuminate the path for a more insightful and connected global community for the generations to come.

Research Sources

The entheomycological origin of Egyptian crowns and the esoteric underpinnings of Egyptian religion

Alcohol and Hallucinogens in the Life of Siberian Aborigines

The History of Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Use Through the Ages

When Did Psilocybin Mushrooms First Appear In Human Culture?

The Oldest Representations of Hallucinogenic Mushrooms in the World

Traditional medicines and globalization: current and future perspectives in ethnopharmacology

The Complicated Ethics of Legalizing Indigenous Psychedelic Substances

Colorado Proposition 122 Election Results: Decriminalize and Regulate Certain Psychedelics

Psychedelic mushroom campaign declares victory on decriminalization in Colorado

Scientists Uncover ‘Strong Relationship’ Between Psychedelic Use And Connection With Nature

On Sacred Reciprocity: Giving Back to our Indigenous Predecessors in the Psychedelic Movement

Footnotes

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mar%C3%ADa_Sabina

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curandera

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shamanism

[4] https://fantasticfungi.com/the-r-gordon-wasson-trip-that-changed-everything/

[5] https://millennialmatriarchs.com/2021/04/22/maria-and-her-magic-mushrooms/

[6] https://chacruna.net/colorado-health-psychedelic-medicine/

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peyote

[9] https://info.drbronner.com/all-one-blog/2022/03/natural-medicine-colorado-combining-regulated-and-community-healing-models/#:~:text=The%20NMHA%20requires,also%20do%20so.

[10] https://www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/elections/Initiatives/titleBoard/filings/2021-2022/58Final.pdf

[11] https://naturalmedicinecolorado.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Initiative-58-.pdf

[12] https://www.cpr.org/2022/10/17/vg-2022-proposition-122-natural-medicine-health-act-psychedelic-substances/

[13] http://www.dailyrx.com/mass-trauma-and-mental-health

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psilocybin

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psilocin

[16] https://psychedelicinvest.com/how-many-different-types-of-psychedelic-mushrooms-are-there/

[17] http://www.artepreistorica.com/2009/12/the-oldest-representations-of-hallucinogenic-mushrooms-in-the-world-sahara-desert-9000-–-7000-b-p/

[18] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227720389_Iconography_in_Bradshaw_rock_art_Breaking_the_circularity

[19] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378874105005131?via%3Dihub

[20] https://singingtotheplants.com/2008/02/hallucinogens-in-siberia/

[21] https://chacruna.net/maria-sabina-mushrooms-and-colonial-extractivism/

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overview_effect

[23] https://psychonautwiki.org/wiki/Cognitive_effects_-_Psychedelics

[24] ‘Conceit’: “an excessively favorable opinion of one’s own ability, importance, wit, etc. something that is conceived in the mind; a thought; idea” — Dictionary.com

[25] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00213-017-4701-y

[26] https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/171699/the-brain-lsd-revealed-first-scans/

[27] https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1918477117#:~:text=Past%20research%20suggests%20that%20use,a%20naturalistic%20setting%20is%20scarce.

[28] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6949937/#:~:text=In%20a%20retrospective%20survey%20of,their%20environmental%20concern%20had%20increased.

[29] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6949937/

[30] https://chacruna.net/psychedelics_indigenous_reciprocity/